In recent years, the language of “mental health” has become deeply embedded in public conversation. When people feel anxious, low, exhausted or disconnected, they may describe themselves as having “depression,” “anxiety,” or a “mental breakdown.” These terms increasingly appear both in search engines and in conversations with primary-care professionals.

During COVID-19, this overlap intensified. Loneliness, grief, uncertainty, isolation, financial strain and emotional exhaustion were widespread. These reactions were human and expected, but the narrative surrounding them was often clinical. This has shaped how people describe distress today and may contribute to a growing public confusion between mental health, mental illness, and chronic stress.

A central question therefore emerges: is the UK facing a mental illness crisis, or a chronic and toxic stress crisis that is being interpreted through the language of mental illness?

Mental Health Exists on a Continuum

Modern psychological frameworks emphasise that mental health and mental illness are not opposites. Leading UK organisations—including the British Psychological Society (BPS), WHO, and NICE—describe mental health as existing on a continuum involving two axes:

- Whether a person has a clinical diagnosis

- Whether that person experiences high or low wellbeing

This produces four possible states, all valid:

- High wellbeing with a diagnosis

- High wellbeing without a diagnosis

- Low wellbeing with a diagnosis

- Low wellbeing without a diagnosis

This framework clarifies a key truth: a person can be distressed, overwhelmed, burnt out or struggling, yet not have a mental illness. Likewise, a person may have a diagnosis yet experience long periods of resilience and good wellbeing.

Mental Illness: Clinical, Diagnosable, Evidence-Based

Clinical conditions—including major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, PTSD, generalised anxiety disorder and personality disorders—are identified through established diagnostic criteria and involve persistent symptoms, impairment and measurable biological/psychological changes.

Research from Oxford, Cambridge, UCL, Stanford and others shows that conditions such as major depressive disorder involve changes in:

- serotonin signalling pathways

- prefrontal cortex regulation

- amygdala reactivity

- hippocampal plasticity

Treatments such as SSRIs and structured psychotherapies are designed to target these specific mechanisms. They are not intended for normal sadness, relationship heartbreak, bereavement, or stress arising from workload or life transitions.

Personality disorder clusters (A, B, C) reflect this same principle: diagnostic categories refer to enduring clinical patterns, not to everyday personality traits or temporary emotional states.

COVID-19, Language, Search Behaviour and Primary Care

During the pandemic, many individuals experienced emotional strain unprecedented in recent decades: loss, uncertainty, isolation, disruption and chronic fear. These emotional experiences were frequently described in clinical language, both online and in personal conversations.

It is important not to assume what GPs said or recommended. However, individuals may have visited their doctor or searched online using terminology such as “depression,” “anxiety disorder,” or “panic attacks” to describe their distress, even when the underlying experience reflected situational stress or normal emotional pain.

This shift in language may partly explain why the UK has seen:

- increased presentations for anxiety- and depression-related concerns

- increased antidepressant prescribing

- increased visibility of emotional suffering expressed in clinical terms

Rising Mental-Health Related Consultations

NHS Digital’s Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (2023–24) reports that 13.2% of adults in England spoke with a GP about a mental or emotional difficulty within the past year—reflecting a notable rise in help-seeking.

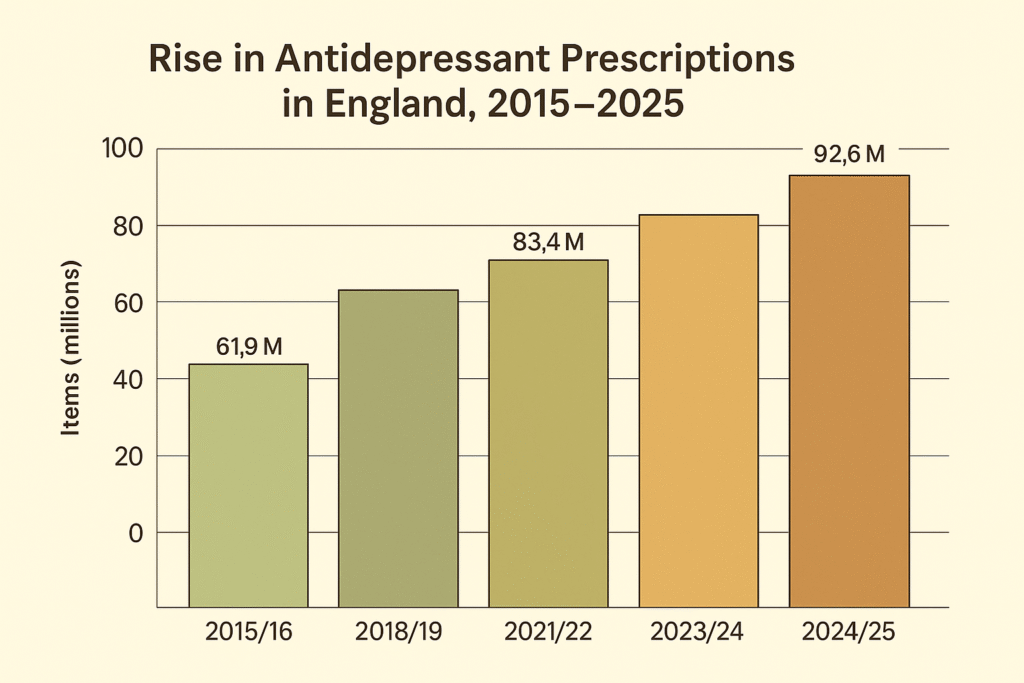

Antidepressant Prescriptions Have Risen Significantly

Multiple high-quality datasets confirm a sustained upward trend:

The bar chart shows a clear and sustained rise in antidepressant prescribing in England over the past decade, increasing from 61.9 million items in 2015/16 to 83.4 million in 2021/22, and reaching 92.6 million in 2024/25. NHS Business Services Authority data confirms a 3.3% year-on-year increase in 2023/24 and highlights that over 8.7 million patients received antidepressants that year. Quarterly NHS figures also show 23 million items dispensed between April–June 2024 alone. Long-term analyses indicate that antidepressant prescribing has more than doubled since 2010, reflecting changing help-seeking behaviours, increased emotional distress, and shifting terminology in how individuals describe their experiences.

Sources:

- NHSBSA 2023/24 Mental Health Medicines Statistics: https://media.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/press-releases/5171d616-95ea-4282-959b-15f8bfed6a0f

- NHSBSA Quarterly Summary (Apr–Jun 2024): https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/statistical-collections/medicines-used-mental-health-england-quarterly-summary-statistics-20242025

- Pharmaceutical Journal — 35% rise in six years: https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/news/antidepressant-prescribing-increases-by-35-in-six-years

- Wiley — Long-term doubling since 2010: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/hup.70011

- NHS Digital — Adult Psychiatric Morbidity 2023/24: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey

These figures reflect a mixture of factors: increased emotional distress, increased help-seeking, longer prescription durations, and the growing use of diagnostic language by individuals when describing stress, overwhelm or situational difficulty.

Are We Facing a Mental Health Crisis—or a Chronic and Toxic Stress Crisis?

Rather than assuming a surge in mental illness, it may be more accurate to ask whether we are experiencing a nationwide chronic stress crisis, driven by:

- digital overload and constant comparison

- loneliness and reduced community cohesion

- economic pressure and precarious living

- work intensification

- social isolation

- disrupted sleep

- reduced time for rest, meaning-making and connection

These pressures produce symptoms that feel like mental illness—irritability, fatigue, low mood, difficulty concentrating, emotional volatility—but are often rooted in chronic stress physiology, not psychiatric conditions.

This distinction is essential for providing the right types of support.

How Chronic Stress Affects the Brain

Why This Distinction Matters

Clear terminology allows for appropriate care:

- Not all distress is illness; not all sadness is depression.

- Many people need support, connection, lifestyle changes, therapy or community—not necessarily clinical treatment.

- Accurate language reduces stigma and helps people understand that emotional difficulty is part of being human.

- It supports clinicians, coaches, therapists and community practitioners in responding with the right intervention at the right time.

What We Can Do: Community, Practitioners, and Individuals Working Together

Addressing chronic stress, emotional overwhelm, and the rising confusion around mental health requires a shared, community-centred approach. While clinical services remain essential for those with diagnosable mental illness, a significant proportion of the population is struggling with stress, loneliness, uncertainty and disconnection. These challenges respond best to relational, social and preventative strategies — not solely clinical pathways.

Below are key ways communities, therapists, organisations, and individuals can work together to build resilience and reduce chronic stress.

1. Strengthening Community Support Systems

Many people experiencing emotional distress do not need clinical intervention — they need connection, support, belonging and safe places to talk.

Communities can create this by:

Expanding local wellbeing hubs

Spaces where people can drop in, talk to a trained listener, join a group activity, explore tools for stress, or simply feel less alone.

Developing more crisis cafés and safe spaces

Non-clinical, calm environments staffed by trained listeners where people can go when overwhelmed — especially during evenings and weekends when distress often escalates.

Building neighbourhood connection

Local groups, coffee mornings, walking groups, youth spaces, parent meet-ups, and community circles help rebuild belonging and reduce social isolation.

Embedding emotional learning into schools, colleges, and workplaces

Normalising discussions about pressure, uncertainty, loneliness and identity promotes earlier support and reduces escalation.

2. What Therapists, Coaches and Practitioners Can Offer

Practitioners play a vital role in bridging the gap between normal distress and clinical diagnosis. They can help individuals understand what they are feeling, why they are feeling it, and whether it requires clinical care or supportive intervention.

Therapists and practitioners can:

Provide language clarity

Helping individuals distinguish between stress, burnout, grief, low mood, anxiety, and clinical mental illness reduces fear and supports appropriate next steps.

Teach emotional regulation and stress management

Evidence-based tools — grounding techniques, cognitive reframing, self-compassion strategies, breathwork, meaning-oriented approaches — help individuals regain balance.

Support meaning, direction, and purpose

Approaches grounded in existential analysis and logotherapy help individuals explore purpose, values, identity and meaning — crucial areas when chronic stress erodes motivation.

Strengthen interpersonal skills and relationship health

Many individuals struggle not because of illness, but because of conflict, loneliness, miscommunication, or relational insecurity. Improving communication and attachment patterns can be transformative.

Encourage community connection

Therapists can guide individuals toward group activities, relationship building, volunteering and meaningful engagement — core antidotes to chronic loneliness and stress.

3. What Individuals Can Do Daily

While systemic change is essential, individuals also benefit from accessible, evidence-informed tools that help manage stress and build resilience.

Create breathable routines

Small daily practices — morning light exposure, 5–10 minutes of breathing, structured breaks, time outdoors — significantly reduce stress load.

Prioritise connection

Regular conversations, shared activities, and simply spending time with others protect against chronic stress.

Practice healthy communication

Clearer communication improves relationships, reduces conflict, and builds emotional safety.

Rebuild meaning and purpose

Engaging in purposeful activities, values-based goals, creativity, helping others, and small acts of growth supports long-term wellbeing.

Use digital tools wisely

Apps and online resources can help when used intentionally rather than reactively.

4. How Meaningful Paths Can Support This Work

Meaningful Paths offers accessible tools that help individuals and communities manage stress and build meaningful, resilient lives. These resources are designed for both early support and ongoing wellbeing, complementing therapeutic work rather than replacing it.

Within the Meaningful Paths app, individuals can explore:

- Stress-management tools

Practical exercises for calming the nervous system and reducing overwhelm. - Communication and relationship skills

Guidance for improving conflict resolution, emotional expression and connection. - Purpose and meaning resources

Activities and reflections grounded in logotherapy and existential analysis. - Healthy habits and emotional wellbeing pathways

Modules that support resilience across everyday life challenges.

These tools help people build skills, insight and emotional strength while reducing reliance on clinical pathways for non-clinical distress.

Conclusion

The UK is experiencing widespread emotional strain, exhaustion, loneliness and chronic stress. The question is not simply whether we face a “mental health crisis,” but whether we are witnessing a chronic and toxic stress crisis that is being interpreted through clinical language.

By distinguishing mental illness from stress, and distress from diagnosis, we create space for compassion, clarity and more effective support. This clarity enables us to respond to genuine mental illness with appropriate treatment, while also recognising the deep need for connection, rest, belonging and stress reduction across the wider population.

References

Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (2023–24). Mental Health Treatment and Service Use. NHS Digital. Retrieved from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey/survey-of-mental-health-and-wellbeing-england-2023-24/mental-health-treatment-and-service-use

British Psychological Society (2018). Understanding Psychosis and Schizophrenia. Leicester: BPS Publications.

British Psychological Society (2020–2023). Position Statements on Mental Health, Diagnostic Language, and Psychological Wellbeing. Leicester: BPS.

Keyes, C. (2002). The Mental Health Continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing in Life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222.

Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R., Stockmann, T. et al. (2022). The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence. Molecular Psychiatry, 27, 2393–2404.

NHS Business Services Authority (2024). Mental Health Medicines Statistics for England 2023/24. Retrieved from: https://media.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/press-releases/5171d616-95ea-4282-959b-15f8bfed6a0f/nhs-releases-2023-24-mental-health-medicines-statistics-for-england

NICE Guidelines. Depression in adults: recognition and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

NICE Guidelines. Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults: treatment and management.

Oxford University (2023). Seasonal patterns of antidepressant prescribing, depression and anxiety consultations in adolescents: A population-based study in UK primary care. BMJ Mental Health / Oxford Research Archive. Retrieved from: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:92ee0e39-076a-42cd-a217-27ddf6026b17/files/szw12z6955

Sapolsky, R. M. (2004–2017). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. New York: Holt Paperbacks. (Foundational neuroscience reference on chronic stress, hippocampal changes, and glucocorticoid effects.)

Sapolsky, R. M. (2015). Stress and the brain. Stanford University Lectures in Human Behavioral Biology.

UCL Institute of Mental Health (2019–2024). Publications on stress physiology, neuroplasticity, and emotional regulation.

World Health Organization (2004). Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice. Geneva: WHO Press.