Written by Dr. Kate Payne and narrated by Aria Edwards.

An article on why children may experience anxiety, how to spot the signs of anxiety in children, and developing tools for them to deal with the ‘big feelings’.

Introduction

Mental health is more than the absence of mental health disorders, the World Health Organisation (WHO) defines it as a state of wellbeing where individuals realise their own potential and can cope with the normal stresses of life. Therefore, it is important to develop resilience and promote mental wellbeing in children to protect them against potential risk factors. Research has shown a continued increase in anxiety in children, and it is estimated that one in eight 5- to 19-year-olds had a mental health disorder in 2017, which is least three children per class[1]. This is important to consider because 75% of mental health difficulties usually develop before the age of 25[2]. During Covid-19, it is thought that anxiety has nearly doubled in young adults compared to pre-pandemic levels[3]. Whilst these stark statistics shed light on the prevalence of anxiety in children, this also provides a window of opportunity to promote social and emotional development to help children manage their feelings.

“Happiness is not the absence of problems; it is the ability to deal with them” – Steve Maraboli

What Can Make a Child Anxious?

Anxiety is a natural physiological response to potentially threatening situations that we all can experience. A small amount of anxiety can be helpful, and we can do better in some situations as a consequence, such as performing in an exam. In the early years, children may experience separation anxiety which means they can become distressed when separated from their primary caregivers. This is a normal part of development and will usually fade before they start school. Throughout a child’s development, they are likely to express feelings of worry about certain things such as being in dark, getting their hair cut, going to the doctors/dentist or an upcoming test. Key transition points also may cause an increase in anxiety, such as a first day at school or starting secondary school. Teenagers are more likely to experience anxiety regarding social relationships and academic pressures. All children will experience worries to some extent and this is a normal and natural part of growing up. It is important to promote emotional literacy in children so that they have the space to talk about how they feel and develop the skills to regulate their emotions.

When Can Anxiety In Children Become A Problem?

Anxiety in children can become a problem when the challenge they are experiencing outweighs their capacity to cope. This builds to the point that the child feels overwhelmed and impacts on their capacity to think, reason, and cope with everyday demands. Significant anxiety over time can influence a child’s overall development and this can impact on educational achievement, relationships, and physical and mental wellbeing. The child may not have a recognised mental health disorder but will need support to understand how they are thinking, feeling, and behaving.

Sources

[1] NHS Digital. Mental health of children and young people in England, 2017: Summary of Key Findings (2018).

[2] Kessler R, Amminger P.G., Aguilar-Gaxiola S., et al. (2007). Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 20, 359–64.

[3] Kwong, A. S., Pearson, R. M., Smith, D., Northstone, K., Lawlor, D. A., & Timpson, N. J. (2020). Longitudinal evidence for persistent anxiety in young adults through COVID-19 restrictions. Wellcome Open Research, 5(195), 195.

All children will have protective factors; these are the positive aspects within a child’s life to promote resilience and act as a buffer against challenges they may experience. Children will also have risk factors which increase their vulnerability to experience difficulties in their mental health (see table below). When considering the potential causes of anxiety for a child, it is important to listen to their views about school, home, friendships, life events, personalities, and beliefs.

| Child factors | Family factors | School factors |

| Temperament Self-confidenceLearning capabilityTraumatic eventsCoping strategies | Socio-economic statusFamily dynamics/conflictParenting stylesParental mental health | Friendships/relationshipsAcademic achievement/demandsTransitionsSchool ethos |

Signs Of Anxiety in Children

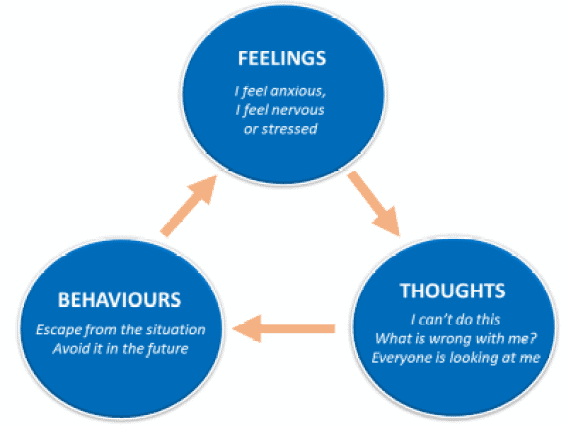

Anxiety can be thought of within a triad, the interaction between the child’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviours (see figure 1). Therefore, it is important to consider the indicators of each of these aspects when spotting signs of anxiety in children.

Feelings

Children can experience physiological responses to anxiety. For example, increase in heart rate, headaches, stomach-aches, pale complexion, dizziness, lack of concentration, a need for the toilet, or sweaty palms. Therefore, if a child appears to be experiencing these reactions, it may be a sign they are feeling anxious.

Thoughts

Children will constantly be thinking; as one thought passes through, another takes its place. Positive thoughts produce pleasant feelings e.g. ‘I am looking forward to the party’. Negative thoughts often produce unpleasant feelings e.g. ‘no one will turn up to my party’. A child experiencing anxiety will likely reveal their ‘self-talk’ through their interactions. Anxious thoughts often consist of statements that are overly negative ‘I only got 6/10 on the test’; spiralling ‘what if…’ statements; or inaccurate mind-reading ‘she doesn’t like me’. It may be possible to spot anxious thinking through their conversations.

Behaviours

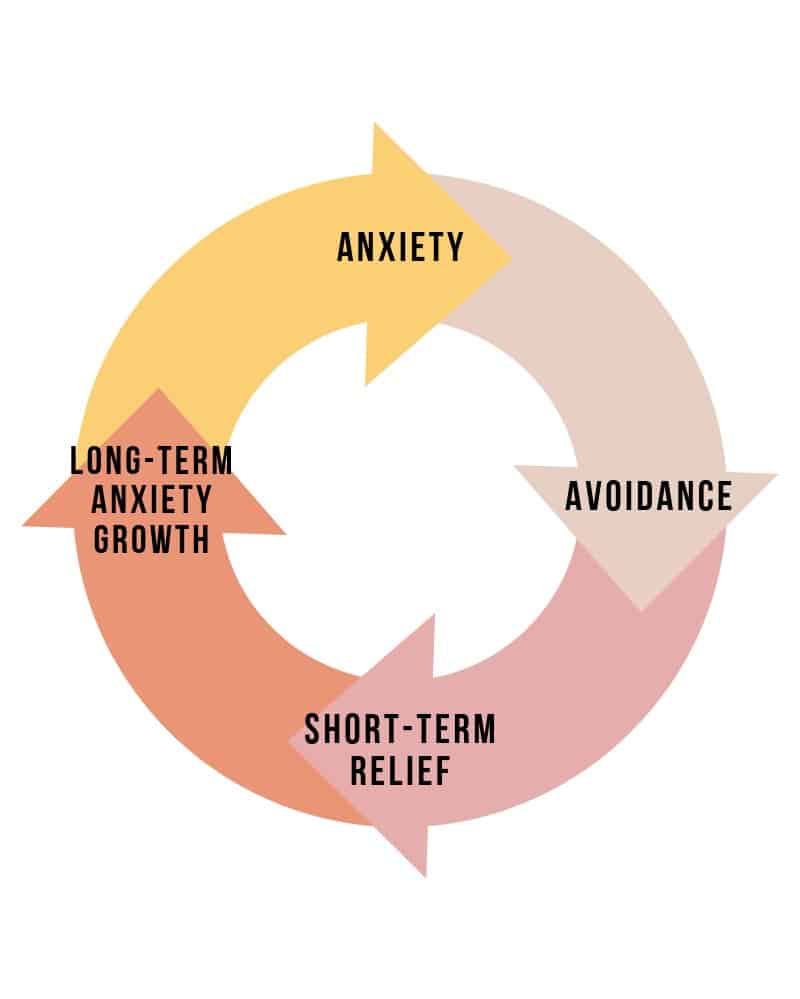

From an evolutionary perspective, humans needed anxiety as a natural response to perceived threat within the environment so their body could instinctively react in a fight, flight, or freeze response. This means that when children experience a trigger which results in heightened anxiety, they can react physically (e.g. kicking, shouting, breaking things), running away from the situation or remaining frozen and internalising how they are feeling. These behaviours within children may indicate elevated levels of anxiety. One of the most common ways of managing anxiety is to avoid the situation as this can provide immediate relief. However, this is only a short-term solution as this can increase anxiety and make it even more difficult to face the situation next time. This is particularly true when a child won’t go to school because of anxiety; they initially avoid the anxious situation, and consequently miss friendships and learning, and so their worry increases, as does their desire to stay at home (see figure 2).

How To Solve Anxiety In Children

To support a child to overcome their anxiety, the following recommendations will be helpful to consider.

Develop emotional literacy: The child may need support to develop their emotional literacy so that they can recognise and understand their emotions. This could involve modelling, labelling, and validating how they are feeling, and what might be happening in their body. For example, “Charlie, I think you may have a tummy-ache because you are feeling worried about your test tomorrow. That is ok, sometimes I get funny feelings in my tummy when I am worried too”.

Providing emotion check-ins: It will be helpful to encourage the child to ‘check-in’ how they are feeling at several points throughout the day so that they can begin to recognise times when they are calm, excited, or anxious. For younger children, this can be visually represented through colours or emoticons and for older children this can be through rating scales or feeling thermometers.

Protected time for communication: Encourage children to talk about how they are feeling so that the adults can support them. Children may be encouraged to think about which worries are within their control, and which are not. It can sometimes be helpful to provide a protected time at the end of the day specifically for discussing worries. Children can then write their worries down during the day to discuss within their ‘special time’.

Gradual exposure: Avoidance of situations causing anxiety is a maladaptive coping strategy and often exacerbates their worries. Therefore, it is important that the child is encouraged to take a small step towards engaging in the anxiety provoking situation. A patient, positive and supportive approach will be needed and consideration for how to make this a successful experience.

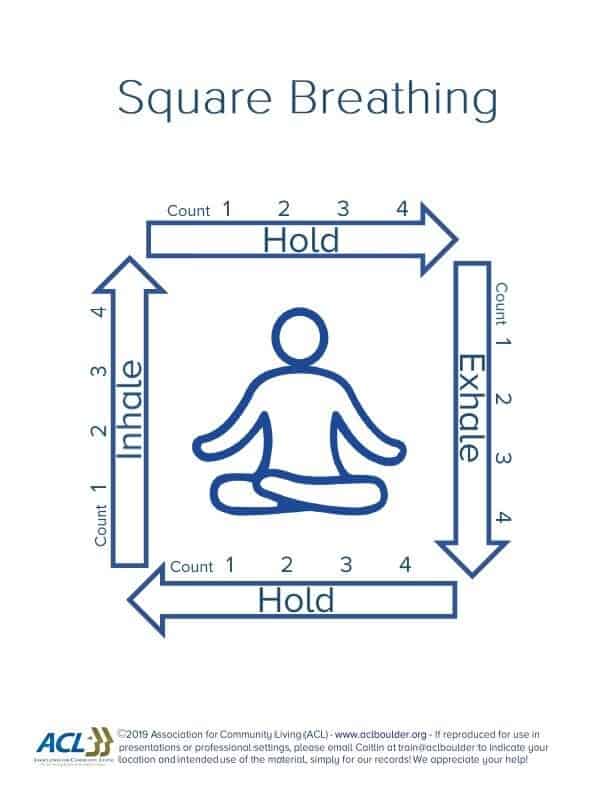

Coping strategies: Children will need to develop a toolbox of strategies to help them to reduce the physiological responses to anxiety ‘in the moment’. These are known as grounding techniques that are helpful to reduce heart rate, distract thoughts, and return the child to a calming state. Children can be taught mindfulness breathing (see figure 3), or encouraged to do the ‘5,4,3,2,1’ check (five things you can see, four things you can feel, three things you can hear, two things you can smell and one thing you can see).

Consider additional support

If anxiety in children is too interfering or persistence, professional help may be required, and the GP will likely be the most appropriate first step.

“It all depends on how we look at things, and not how they are in themselves” – Carl Jung

Main Image Reference

tanaphong-toochinda-GagC07wVvck-unsplash